The case for universal support for European families

Austerity measures introduced during the crisis have disproportionately concerned cuts in the measures that are most vital for reducing child poverty: cash and tax benefits, a new Eurofound report shows. Furthermore, there has been a move away from universal coverage towards more targeted support. Of course, it makes good sense for governments to target spending on the most deprived families in a period of austerity. But at some point the pendulum can swing the wrong way and families that, under the principle of universality, were eligible for support may lose out, putting more families at risk of poverty than before.

It should be said that the principle of universality prevailed during the crisis as universal cash benefits still represented more than half of the social expenditure on families in the EU, followed by universal benefits in-kind such as childcare services (the figures are for 2011, the latest year for which data was available at the time of writing the report). Means-tested cash benefits and means-tested benefits in-kind represented less than one-quarter of the total social expenditure on families. Although universal support remained the preferred approach over targeted help in most Member States, how countries support families varies strongly.

No surprises here: the three Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland and Denmark) did best. There, support for families was universal and Sweden and Finland offered families a perfect mix of cash and in-kind support (in Denmark the scale tipped in favour of universal in-kind benefits).

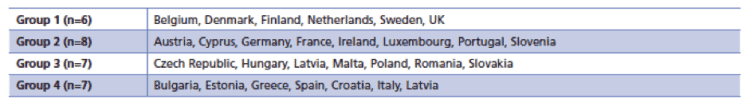

Table 1 shows the countries belonging to our four family policy country groups which Eurofound developed to account for large differences in family policy pathways in Europe. The countries belonging to Group 1 most enable families to move away from the traditional ‘breadwinner’ model, where it is the mother who stops working or reduces her hours to look after the children; in countries belonging to Group 4, family policies are most limiting in this regard.

Table 1: Eurofound family policy country groups

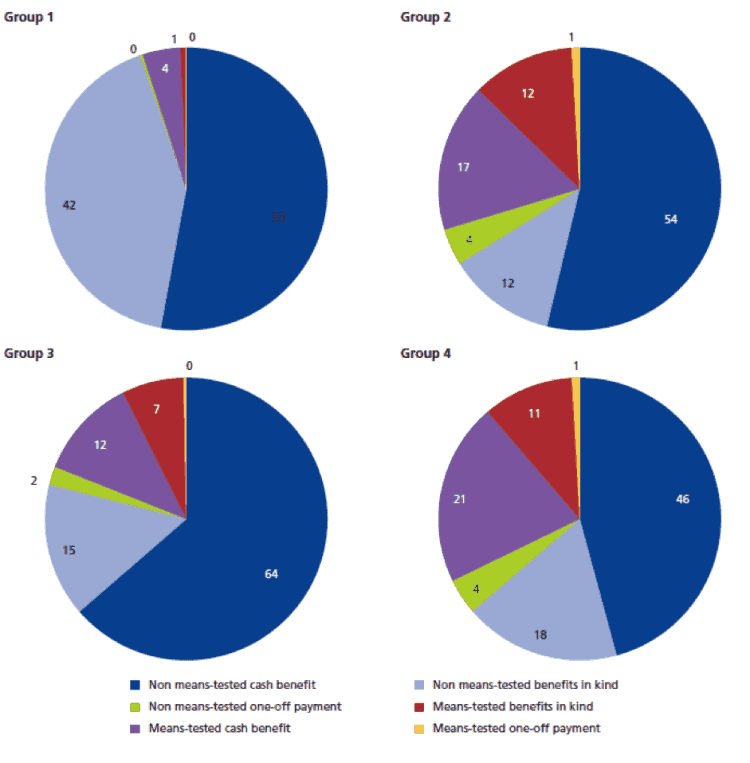

Figure 1 below shows the structure of social expenditure on families for these four groups of EU Member States. As can be seen, universal support is the norm in Group 1 countries with a good balance between cash and in-kind benefits. While universal support is also the norm in Group 2 countries, in-kind benefits are far less common and these countries are much more like the two groups with more limiting family policies.

Fig. 1: Structure of social expenditure on families by country groups (2011, %)

Source: Own calculations based on ESSPROS

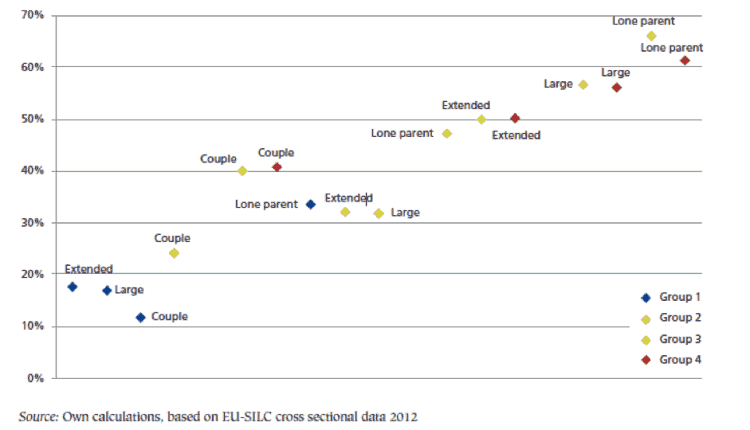

These expenditure patterns are to some degree mirrored in the extent to which different types of families report difficulties making ends meet. As figure 2 below shows, on average, the family types in the countries with more ‘enabling’ family policies (Groups 1 and 2) report fewer difficulties than those in the countries with more ‘limiting’ family policies (Groups 3 and 4).

Figure 2: ‘Difficulties making ends meet’ rate by family type and country group, 2012 (%)

However, analyses from Eurofound’s 2nd and 3rd wave of the European Quality of Life Survey (fielded in 2007 and 2011/2012, providing insight into the economic and social changes occurring in Europe during the crisis) show that the share of lone parent families in Group 1 and Group 2 countries that reported difficulties making ends meet increased significantly (it doubled in Group 1 countries from 22% to 44% and rose from 37% to 50% in Group 2 countries). Although at 63% and 67%, respectively, the situation in Group 3 and Group 4 countries is still worse, the differences between more ‘enabling’ countries and more ‘limiting’ countries in 2012 are far less extreme than they were in 2007.

The case of Finland

What could explain this shift? One explanation lies in the change in policy pathways that is noted in some of the Group 1 countries. What’s happening in Finland provides some insights. After a number of expansionary measures that did not indicate an ‘austerity pathway’, the situation in Finland has recently changed. The low overall poverty rate among Finnish families is in part the outcome of a universal child benefit allowance that has long been viewed by experts and recipients alike as playing an important role in preventing it. The question is whether the low poverty rates in Finland will be maintained now that child benefit has been cut and the new government programme envisages further cutbacks in family policy. Experts expect the reductions to hit family income with higher poverty rates a likely outcome. This is aggravated by the fact that family transfers were not indexed until 2011, so their purchasing power had already declined. Already, there is some evidence in the statistics: the latest available Eurostat figures (2014) reveal a decrease in real gross disposable household income (GHDI).

The case for universal support

At the same time, means-tested social assistance in Finland has gradually been increased since 2011. Research in Finland has found a link between the gradual increase in the amount of social assistance and the economic well-being of families in the lowest income quintile. This link suggests that these increases have been an effective countermeasure to poverty among the lowest income families.

Whilst means-tested support is a good way to help the most vulnerable, the trend among EU Member States to move away from universal support and towards more targeted support needs to be monitored precisely because of what is happening in Finland. The changes there represent a major shift in policy orientation. The Finnish proposal to restrict entitlement to public childcare is further evidence of this shift.

Work-life balance initiatives are less affected

Eurofound’s report also contains good news: during the crisis years the focus on work-life balance has been maintained. The report, which looks at what countries did for European families since 2010 in response to the crisis, highlights that across the EU measures have been introduced to help people better combine work and family life. Several examples of these good practices are identified: e.g. the daycare centre and kindergarten funding scheme set up in Greece to provide affordable childcare service, the expansion of childcare services in Poland and new variants introduced in Austria giving parents more options to take parental leave. Aside from these work-life balance measures, the report identifies a number of other policy measures that appear to work in avoiding poverty or social exclusion for families with dependent children.

Related links

Report: Families in the economic crisis: Changes in policy measures in the EU

Survey: European Quality of Life Survey

Author

Daphne Ahrendt

Senior research managerDaphne Ahrendt is a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit at Eurofound. She is the coordinator of the survey management and development activity. In 2020, she initiated Eurofound’s Living and Working in the EU e-survey and now leads the 2026 European Quality of Life Survey, which she has worked on since the survey started in 2003. With over 30 years of experience in international survey research, she is also a member of the GESIS Scientific Advisory Board. Beyond surveys, her substantive research focuses on social cohesion, trust and the inclusion of persons with disabilities. Daphne started her career at the National Centre for Social Research in London where she worked on the International Social Survey Programme before moving to the Eurobarometer Unit at the European Commission. She holds a Master's degree in Criminal Justice Policies from the London School of Economics and a Bachelor's degree in Political Science from San Francisco State University.

Related content

27 January 2016

Throughout Europe families have felt the effects of the economic crisis that began in 2008. This report describes their experience in the aftermath of the crisis, up to the present. It looks in detail at developments in 10 Member States that were selected to represent different types of family policy regime, ranging from those with the most ‘enabling’ policies (which help families move away from the traditional single ‘breadwinner’ model) to those with the most ‘limiting’ policies (which do not). The report analyses Member States’ responses to the crisis. The findings show that changes in family policy since 2010 are largely the result of a range of conflicting issues: the evolution of family needs; demands for austerity cuts; and the need for equitable distribution of limited resources. Such conflict means that family policies often lack an integrated policy framework. In some countries, benefits have been reduced, disproportionately affecting disadvantaged families; in others, new measures have been targeted at the most severely hit. In summary, this report provides policymakers with evidence from different country settings on what policy measures appear to work to mitigate the risk of poverty or social exclusion for disadvantaged families with dependent children. An executive summary is available - see Related content.

Rounds available: