Does the new telework generation need a right to disconnect?

Whatever the benefits of telework – and there are many, including more flexible working time, increased productivity and less commuting – there are drawbacks, as many of the one-third of Europeans who were exclusively working from home during the pandemic will attest. Primary among these is the ‘always on’ culture that telework engenders, encouraging workers to respond to emails, phone calls and texts from work long after the working day or week has ended. This situation may be aggravated if the organisational culture at work incentivises employees to accept heavy workloads and put in overtime, often unpaid. All of which upsets work–life balance, leading to conflicts between work and home life, insufficient rest and health problems like work-related stress and sleep disorders.

Concerns about the impact of telework on the mental health and work–life balance of workers are not unique to this period of pandemic, but the explosion in working from home has certainly focused policy attention on them, and this had led to a debate around the right to disconnect. Yet to be formally conceptualised, it can be described as the right of workers to switch off their digital devices after work without facing negative consequences for not responding to communications from bosses, colleagues or clients. The idea is not new and already had some time in the spotlight when France adopted legislation on the issue in 2016.

Member States following diverse paths

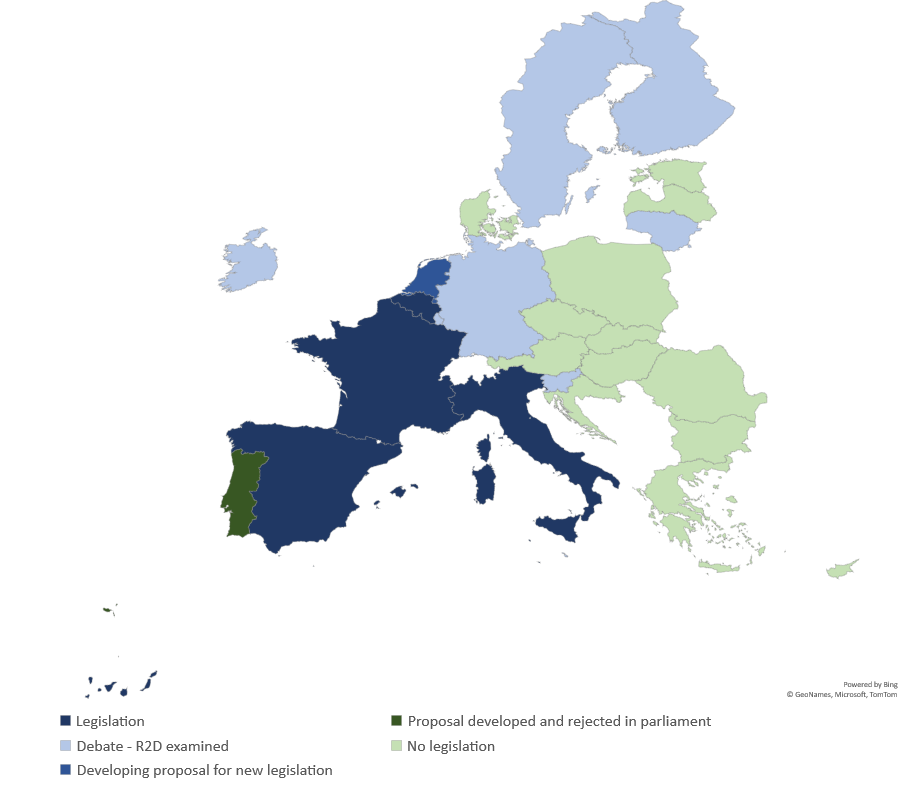

Apart from France, just three other countries – Belgium, Italy and Spain – currently have a right to disconnect on the statute book. None prescribe the way this right has to be operationalised and rely on social dialogue within companies and at sector level to do so. Differences exist between them in terms of which workers are covered by the legislation and the existence of a fall-back option should negotiations fail to reach an agreement – the French legislation, for instance, in this event requires the employer to draw up a charter defining the procedures for exercising the right.

In the Netherlands and Portugal, legislative proposals have been made, but the process is stalling. A further eight countries (Finland, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovenia and Sweden) are debating the issue, with discussions being most advanced in Germany, Malta and Ireland, where legislative proposals have been put forward in recent weeks. In some of these countries, the debate has resurfaced with the expansion of teleworking during the pandemic.

In the remaining 13 Member States, there is no debate on the matter. This may be due to the low prevalence of telework, as is the case in most eastern European Member States, or to the perception that existing legislation is sufficient, or because collective bargaining is the preferred approach to dealing with matters of work–life balance.

We did not identify any evaluations of the impact of the existing right to disconnect provisions in national legislation and without evalutations, it is difficult to know what is working and what is not working in each country. However, there is evidence that these provisions have helped to boost collective bargaining on the issue, resulting in more agreements signed both at sectoral and company levels.

Working paper: Right to disconnect in the 27 Member States

Figure: Right to disconnect and national legislation: Status in the 27 EU Member States

Source: Eurofound, based on contributions by the Network of Eurofound Correspondents and the European Commission

Action at company level

Agreements reached by the social partners at company level implement a variety of hard and soft measures to apply the right to disconnect. Hard measures include shutting down employees’ internet connections after a certain time or blocking incoming messages – effectively a ‘right to be disconnected’. Softer measures include pop-up messages reminding workers (or clients) that there is no requirement to reply to emails out of hours. Such softer approaches are often accompanied by training emphasising the importance of work–life balance. While the different approaches provide companies with the flexibility to tailor solutions to their needs, the implications and impact differ. A hard approach can be more effective and places the onus on the employer, but it may limit the flexibility of both employers and workers around working time. On the other hand, a softer approach relies on the employee to disconnect, which they may be reluctant to do if it is seen as betraying a lack of ambition, which might harm their career.

Notwithstanding national differences, there is a broad consensus among the social partners that the issue of disconnection, as well as the organisation of working time in remote working, have to be determined and agreed through social dialogue at company or sectoral level to ensure that they are adapted to the specific needs of sectors and companies. However, in Member States with low unionisation and infrequent collective bargaining, such an approach could create an uneven playing field.

Legislation at EU level?

In a resolution adopted on 1 December, MEPs in the Employment Committee of the European Parliament stated that Member States must ensure that workers are able to exercise the right to disconnect effectively, including by means of collective agreements. Adding that this right is vital to protect workers’ health, they called on the Commission to propose an EU directive enshrining the right. This non-legislative resolution is expected to be voted on in a plenary session in January 2021. Once endorsed by the Parliament, it will be put forward to the Commission and Member States for implementation as part of future regulatory decisions.

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked a new debate in many countries about extending flexible working (including teleworking) to more workers, it is likely that discussions on the right to disconnect will become more pressing as the ‘new normal’ of working life unfolds. The increase in the number of collective agreements reached and actions taken at company level in countries with legislation on the issue demonstrate not only the important role for the social partners, but also that legislation can provide an impetus for the issue to be tackled, which can still be open to adaptation to specific requirements at company level.

Image © Syda Productions/Adobe Stock

Authors

Oscar Vargas Llave

Senior research managerOscar Vargas Llave is a senior research manager in the Working Life unit at Eurofound and manages projects on changes in the world of work and the impact on working conditions and related policies: organisation of working time, remote work, the right to disconnect, health and well-being and ageing. Before joining Eurofound in December 2009, he worked as project coordinator in the field of health and safety and was responsible for the Professional Card Scheme for the Construction Sector in Spain at the non-profit Fundación Laboral de la Construcción in Madrid. He has a background in industrial sociology (Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca), and also holds a Diploma in Social Science Research Methods from the University of Cardiff and a Master’s degree in Health and Safety from the Autonomous University of Madrid.

Tina Weber

Senior research managerTina Weber is a senior research manager in Eurofound’s Working Life unit. Her work has focused on labour shortages, the impact of hybrid work and an ‘always on’ culture and the right to disconnect, working conditions and social protection measures for self-employed workers and the impact of the twin transitions on employment, working conditions and industrial relations. She is responsible for studies assessing the representativeness of European social partner organisations. She has also carried out research on European Works Councils and the evolution of industrial relations and social dialogue in the European Union. Prior to joining Eurofound in 2019, she worked for a private research institute primarily carrying out impact assessments and evaluations of EU labour law and labour market policies. Tina holds a PhD in Political Sciences from the University of Edinburgh which focussed on the role of national trade unions and employers’ organisations in the European social dialogue.

Related content

12 November 2020

Europe’s quiet revolution is under way

27 September 2020

Living, working and COVID-19

This report presents the findings of the Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey, carried out by Eurofound to capture the far-reaching implications of the pandemic for the way people live and work across Europe. The survey was fielded online, among respondents who were reached via Eurofound’s stakeholders and social media advertising. Two rounds of the e-survey have been carried out to date: one in April, when most Member States were in lockdown, and one in July, when society and economies were slowly re-opening.

The findings of the e-survey from the first round reflected widespread emotional distress, financial concern and low levels of trust in institutions. Levels of concern abated somewhat in the second round, particularly among groups of respondents who were benefiting from support measures implemented during the pandemic. At the same time, the results underline stark differences between countries and between socioeconomic groups that point to growing inequalities.

The results confirm the upsurge in teleworking across all countries during the COVID-19 pandemic that has been documented elsewhere, and the report explores what this means for work–life balance and elements of job quality.

16 January 2020

Telework and ICT-based mobile work: Flexible working in the digital age

Advances in ICT have opened the door to new ways of organising work. We are shifting from a regular, bureaucratic and ‘factory-based’ working time pattern towards a more flexible model of work. Telework and ICT-based mobile work (TICTM) has emerged in this transition, giving workers and employers the ability to adapt the time and location of work to their needs. Despite the flexibility and higher level of worker autonomy inherent in TICTM, there are risks that this work arrangement leads to the deterioration of work–life balance, higher stress levels and failing worker health. This report analyses the employment and working conditions of workers with TICTM arrangements, focusing on how it affects their work–life balance, health, performance and job prospects. While policymakers in many EU countries are debating TICTM and its implications, the study finds that only a few have implemented new regulations to prevent TICTM from having a negative impact on the well-being of workers.