Shaping the future of long-term care: A good outcome will benefit all

An ageing Europe and rising public expenditure on long-term care have signalled for some time that the fundamentals of care provision need to be addressed. However, the shocking death toll in care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that many long-term care services were ill-equipped to protect their vulnerable users have lately focused the public mind on the issue. Most people in the EU will need such care for themselves or someone close to them at some stage in their lives. Demand is already escalating, as the rise in the long-term care workforce – by a third in just a decade – testifies. Calls for a European care strategy rightly insist that care users be listened to, but here we highlight others in the system whose needs deserve attention too.

Carers need more support

Informal carers play a significant role in long-term care provision in all countries: a staggering 44 million people (12% of the adult population) provide such care to family or friends regularly. This compares to 6.3 million people working in the long-term care sector. [1]

This means that even if formal services expand enormously, informal care is here to stay. However, a smart care policy should look for an optimal balance between formal services and informal caring. It must ensure that care receivers get quality support while enabling their carers to continue in work and avoid social exclusion.

The Work–Life Balance Directive (2019) is one block in building such a system. It establishes a right to flexible work arrangements for carers and provides for carer’s leave of at least five days a year. If informal care is not supported by appropriate services, however, some carers may be unable to stay in employment or, if not already employed, to take up a job. Furthermore, this directive is targeted only at people in employment, so its provisions do not apply to the many carers who are retired, many of whom suffer ill health and social exclusion as a result of their care responsibilities.

Flexible respite care services that respond to the needs and preferences of care users and informal carers are part of the answer. They provide a planned, structured break from care responsibilities and should help carers to maintain their quality of life as well as the quality of care they provide. While not all Member States provide such services, they have at least begun to discuss the subject. [2]

COVID-19 has increased pressure on many informal carers, partly because alternative care options, such as visits by home-care workers and use of residential care facilities, were curtailed due to the risks to care users, and to care workers too.

Domestic care needs to be regularised

Trust in residential care is likely to have been undermined by the high mortality rates in these facilities from COVID-19, and this may shift people’s preferences to home- and community-based care. Some households might opt for domestic carers, employed directly by a household.

Domestic care is not without challenges. More often than other long-term care work, it is undeclared, so workers are not covered by social insurance if they lose their jobs or cannot work due to illness. Being in this irregular situation no doubt meant many struggled this year: in mid-April 2020, half of domestic workers in northern, southern and western Europe had suffered reduced hours or job loss during the COVID-19 crisis. [3] Furthermore, domestic carers do not have the right to sick leave, which can result in them showing up for work even if ill (‘presenteeism’), an issue that has not been addressed by policy.

It is possible to regularise domestic care, as Austria and Italy have demonstrated. It is also possible to reduce the need for the types of domestic care that typically have the worst working conditions – live-in care particularly – as several other countries have done, by providing good access to high-quality home and community care services.

There is a gender-equality dimension

In any scenario that involves developing access to care in the future, consideration must be given to the striking gender imbalances in the sector, namely that women account for the majority of long-term care workers and informal carers as well as people with long-term care needs. If access to long-term care improves, this will have a direct positive effect on gender equality by reducing the burden on informal carers and improving care for users. However, more needs to be done for it to benefit the many female workers in this sector, especially in terms of their working conditions, and for this pay off in terms of the quality of care they give.

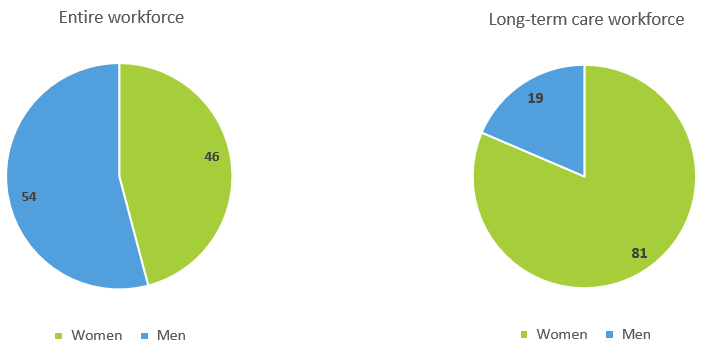

More than four out of five long-term care workers are female – more than in healthcare (75%) or the entire workforce (46%) (see the figure below) – and this has barely changed over the past decade. [4] These workers experience considerable emotional strain and adverse social behaviour on the part of care users, which leads to heightened mental health risks. In a growing sector, this is of great concern, and paying insufficient attention could exacerbate gender inequality in mental health. Such mental health problems also come at a high cost if they are not addressed appropriately. Already, the cost to taxpayers is estimated to be 4% of the EU’s annual GDP. [5]

Figure: Long-term care workforce, by gender, compared with the entire workforce, EU27 and the UK, 2019 (%)

Source: EU-LFS, Eurofound analysis; see References, no. 1.

Finally, think prevention!

Future care users are likely to agree that it’s better to prevent, or at least postpone, the need for care. For this to be possible, action needs to come from areas beyond the care services sector. For instance, previous research by Eurofound has pointed to the importance of high-quality housing and neighbourhoods, enabling people to live longer in the community. Good access to healthcare can help too: early intervention by home-care services with people who have modest care needs should be a priority, as early signalling can help to head off further care needs.

Image © De Visu/Adobe Stock

References

^ Eurofound (forthcoming), Long-term care workforce: Employment and working conditions.

^ Eurofound (2020), Access to care services: Early childhood education and care, healthcare and long-term care.

^ ILO (2020), Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on loss of jobs and hours among domestic workers , 15 June.

^ See 1 above.

^ OECD (2018), Health at a glance: Europe 2018 – State of health in the EU cycle.

Authors

Tadas Leončikas

Head of UnitTadas Leončikas is Head of the Employment unit at Eurofound since September 2022. Prior to this, he was a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit, managing the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) and developing Eurofound's survey research. Since joining Eurofound in 2010, he has worked on various topics including survey methods, quality of life, social mobility, social inclusion, trust and housing inadequacies. In his earlier career, he headed up the Institute for Ethnic Studies in Lithuania where he worked on studies related to the situation of ethnic minorities, migrants and other vulnerable groups. As a researcher, he has previously collaborated with the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, the United Nations Development Programme and the International Organization for Migration. He has a PhD in Sociology.

Hans Dubois

Senior research managerHans Dubois is a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit at Eurofound. His research topics include housing, over-indebtedness, healthcare, long-term care, social benefits, retirement, and quality of life in the local area. Prior to joining Eurofound, he was Assistant Professor at Kozminski University (Warsaw). He completed a PhD in Business Administration and Management at Bocconi University (Milan), after working as a research officer at the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (Madrid).

Related content

25 March 2021

Wages in long-term care and other social services 21% below average

Watch the webinar: Putting care at the heart of Europe – Towards a European Care Strategy

14 December 2020

Long-term care workforce: Employment and working conditions

The long-term care (LTC) sector employs a growing share of workers in the EU and is experiencing increasing staff shortages. The LTC workforce is mainly female and a relatively large and increasing proportion is aged 50 years or older. Migrants are often concentrated in certain LTC jobs. This report maps the LTC workforce’s working conditions and the nature of employment and role of collective bargaining in the sector. It also discusses policies to make the sector more attractive, combat undeclared work and improve the situation of a particularly vulnerable group of LTC workers: live-in carers. The report ends with a discussion and policy pointers on addressing expected staff shortages and the challenges around working conditions.

8 October 2020

Access to care services: Early childhood education and care, healthcare and long-term care

The right of access to good-quality care services is highlighted in the European Pillar of Social Rights. This report focuses on three care services: early childhood education and care (ECEC), healthcare, and long-term care. Access to these services has been shown to contribute to reducing inequalities throughout the life cycle and achieving equality for women and persons with disabilities. Drawing on input from the Network of Eurofound Correspondents and Eurofound’s own research, the report presents an overview of the current situation in various EU Member States, Norway and the UK, outlining barriers to the take-up of care services and differences in access issues between population groups. It pays particular attention to three areas that have the potential to improve access to services: ECEC for children with disabilities and special educational needs, e-healthcare and respite care.

14 December 2018

Striking a balance: Reconciling work and life in the EU

How to combine work with life is a fundamental issue for many people, an issue that policymakers, social partners, businesses and individuals are seeking to resolve. Simultaneously, new challenges and solutions are transforming the interface between work and life: an ageing population, technological change, higher employment rates and fewer weekly working hours. This report aims to examine the reciprocal relationship between work and life for people in the EU, the circumstances in which they struggle to reconcile the two domains, and what is most important for ;them in terms of their work-life balance. The report draws on a range of data sources, in particular the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) and the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS).