Vaccine acceptance hinges on transparent communication

Vaccine acceptance is key to the success of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns worldwide. Worryingly, over a quarter of people living in Europe are hesitant about taking a COVID-19 vaccine, and the level of hesitancy is especially high among heavy users of social media. The spread of misinformation on social media is an obstacle to reaching the goal of herd immunity against the coronavirus. Strategies to communicate clear and unbiased political and scientific information are needed to counter the effect of misinformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted our lives for well over a year. Many measures have been put in place to try to curb the spread of the virus. At individual level, people have adopted social distancing, hand washing and mask wearing. Schools, workplaces and businesses have changed their practices or closed their doors, and travel has been restricted. The hope that these measures can be eased rests on the successful rollout of COVID-19 vaccines.

Reaching vaccination targets has been difficult despite the triumphant development of new vaccine technologies. Developing, testing, authorising, manufacturing, allocating and disseminating vaccines is a Herculean task. The challenges are amplified as countries race against time to deal with the emergence of new virus variants and to reach herd immunity against the virus.

Lack of public confidence in and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines could prove to be another major hurdle. Over a quarter (27%) of people living in Europe say that they are unlikely to take the COVID-19 vaccine. This hesitancy varies by country and by individual characteristics, including age, gender and educational level. Some of the starkest differences in vaccine hesitancy can be seen between people who use social media heavily and those who do not.

Vaccine refusal most common among heavy social media users

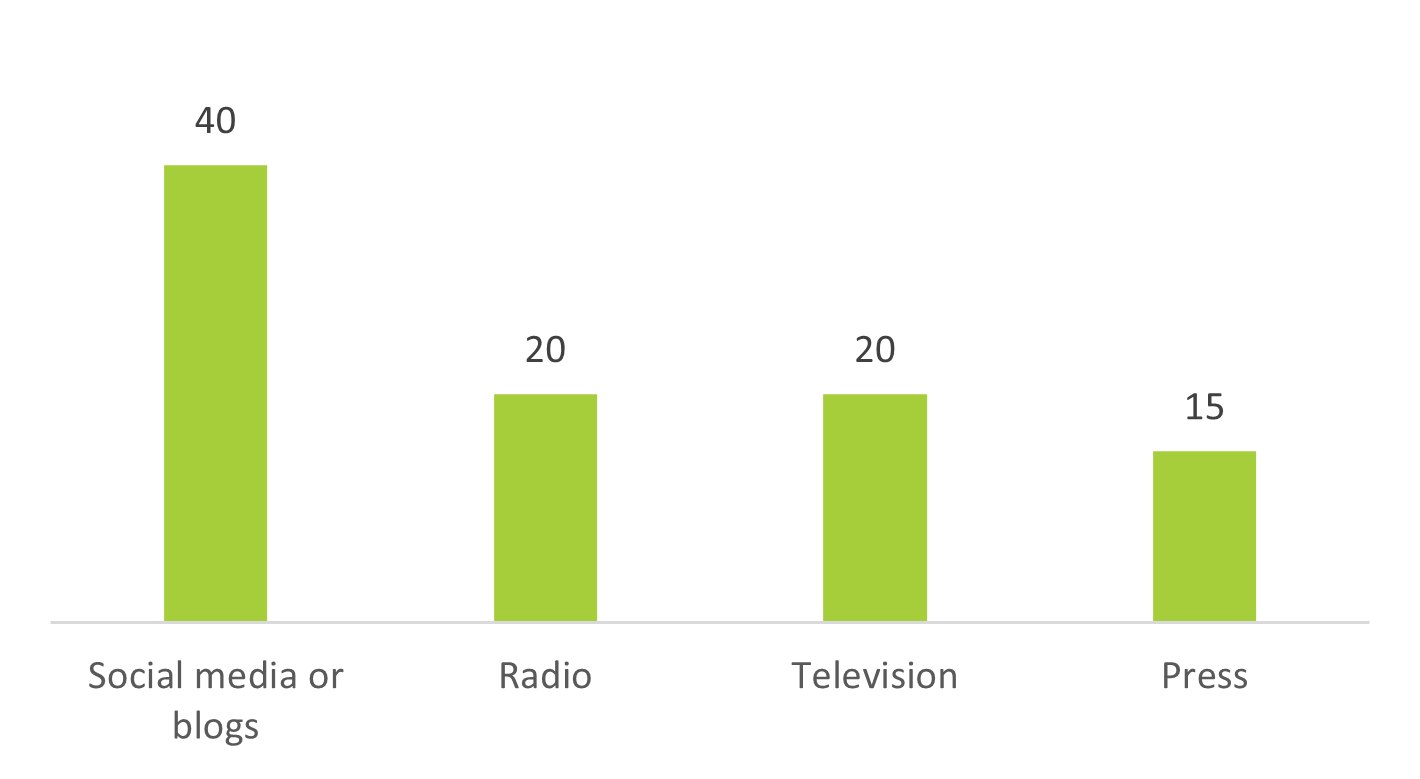

As Figure 1 shows, vaccine hesitancy is most common among people whose main source of news is social media or blogs, with 40% of this group saying they are unlikely to take a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available to them. In contrast, in the combined group of people who use traditional media (radio, television or the press) as their main source of news, under one-fifth (18%) say they are unlikely to accept a vaccine. Even when the impact of factors such as age, gender and health status is taken into account, the differences seen by main news source are statistically significant.

Figure 1: Vaccine hesitancy by main news source (%), EU27, February–March 2021

Note: The survey question was ‘How likely or unlikely is it that you will take the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available to you?’ The chart shows the percentages who answered ‘rather unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’.

Source: Eurofound, Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey, round 3

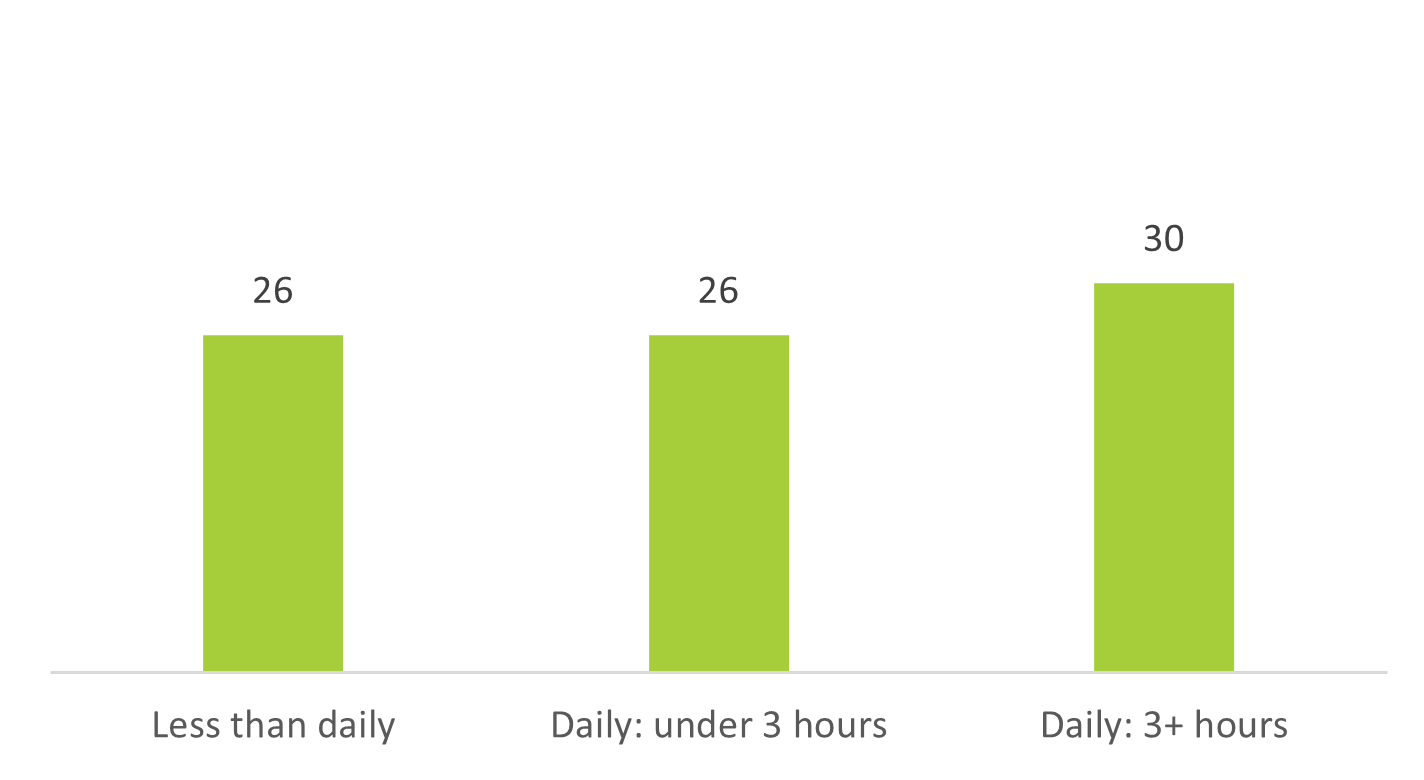

COVID-19 vaccine refusal is also common among people who spend a lot of time on social media. As shown in Figure 2, vaccine hesitancy is greatest among people who spend more than three hours daily on social media: 30% of this group say they are unlikely to get vaccinated. Among people who spend less time on social media, 26% are vaccine hesitant. Again, differences remain statistically significant even when the impact of individual characteristics is accounted for.

Figure 2: Vaccine hesitancy by level of social media use (%), EU27, February–March 2021

Note: The survey question was: ‘How likely or unlikely is it that you will take the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available to you?’ The chart shows the percentages who answered ‘rather unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’.

Source: Eurofound, Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey, round 3

These findings suggest how misinformation about vaccines and COVID-19 spread by social media platforms can shape people’s views about vaccines. They also underline the need for unbiased information so that people can make balanced decisions and disregard misinformation.

Peak in vaccination hesitancy coincides with AstraZeneca suspensions

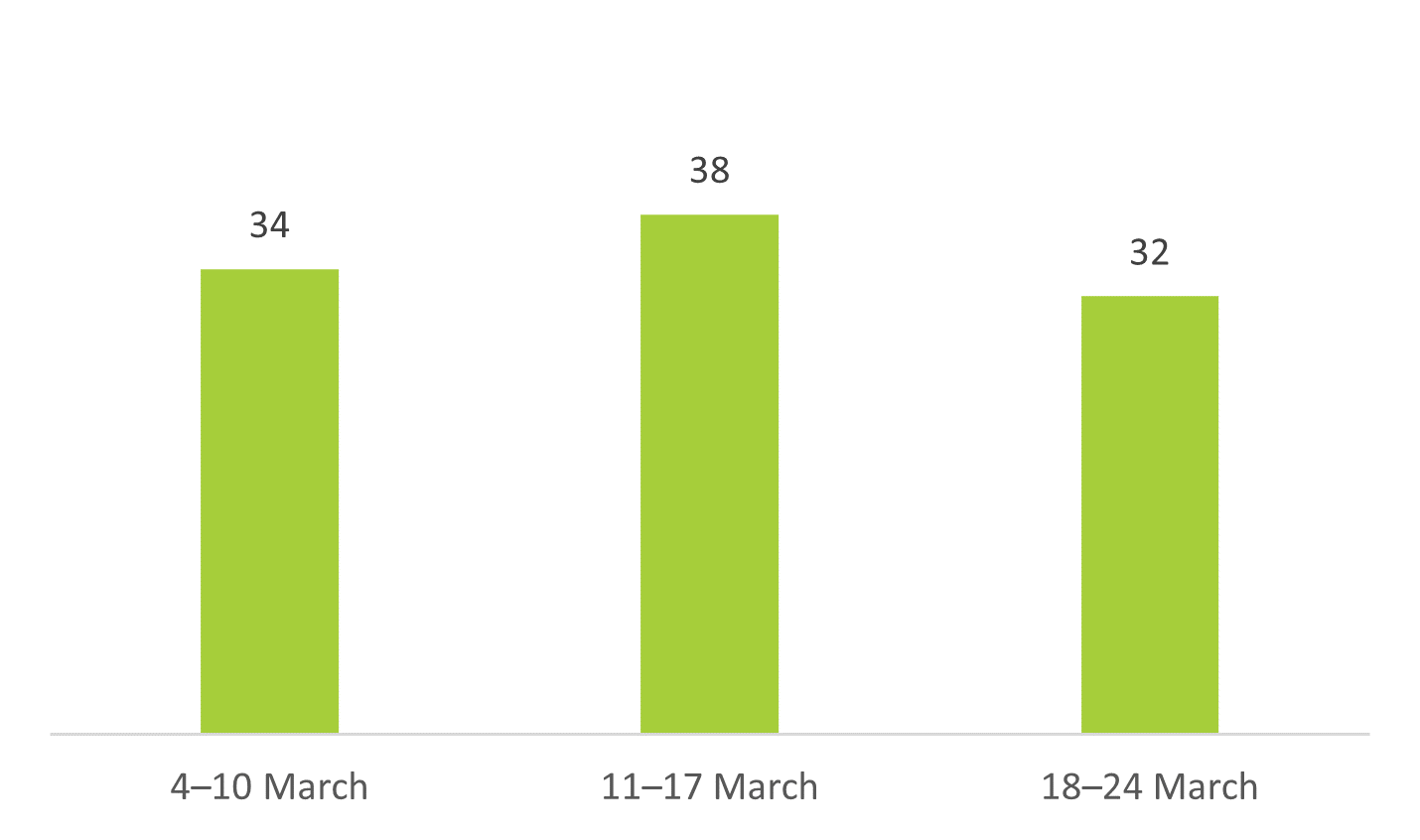

Many EU countries suspended the rollout of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in March 2021, following reports that a very small number of people had developed blood clots after receiving it. Many of the suspensions in Europe were announced on 11 March. Vaccine hesitancy was at its lowest in February but peaked in the week following the suspensions. Figure 3 focuses on the time around the suspensions. It shows that 34% of Europeans were vaccine hesitant in the week prior to 11 March, and this share rose to 38% in the week following the suspensions. Many countries lifted the suspensions after the European Medicines Agency (EMA) declared the vaccine safe on 18 March. In the week following EMA’s announcement, the hesitancy rate fell back to 32%. This volatility in attitudes shows the immediate impact that the availability of new information can have.

Figure 3: Vaccine hesitancy around the time of AstraZeneca suspensions (%), EU27, March 2021

Note: The survey question was: ‘How likely or unlikely is it that you will take the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available to you?’ The chart shows the percentages who answered ‘rather unlikely’ or ‘very unlikely’.

Source: Eurofound, Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey, round 3

Communicating clearly about vaccine safety

Even in the absence of misinformation, humans can be failed by their intuition when assessing risks and probabilities. It can be difficult to weigh up a very small risk of a serious adverse reaction to a vaccine against a small risk of developing a serious illness without a vaccination. In addition, people need to take into account the efficacy of the various vaccines, and the impact that their decision on immunisation will have on the risks faced by the wider population.

Complete transparency in communication builds public trust in vaccines. Providing clear and unbiased information about their safety and effectiveness is crucial for the success of vaccination programmes globally. But making information available does not go far enough. Getting unbiased information across to people who do not use mainstream media presents a challenge. On the upside, social media can be used to help defeat the virus. They can serve as forums in which policymakers and public health officials – and people in general – can provide information and engage with people to address their concerns, hopefully alleviating the hesitancy around vaccination.

Image © cherryandbees/Adobe Stock Photos

Authors

Sanna Nivakoski

Research officerSanna Nivakoski is a research officer in the Social Policies unit at Eurofound. Before joining Eurofound in 2021, she worked as a post-doctoral researcher at University College Dublin's Geary Institute for Public Policy, the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin, and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. She has worked in many research areas in microeconomics, including retirement income and wealth, pension saving, intergenerational transfers and the financial impact of widowhood. Sanna holds a PhD in Economics from Trinity College Dublin.

Massimiliano Mascherini

Head of UnitMassimiliano Mascherini is Head of the Social Policies unit at Eurofound since October 2019. He joined Eurofound in 2009 as a research manager, designing and coordinating projects on youth employment, NEETs and their social inclusion, as well as on the labour market participation of women. In 2017, he became a senior research manager in the Social Policies unit where he spearheaded new research on monitoring convergence in the EU. In addition, he led the conceptualisation of the 2026 European Quality of Life Survey. In 2025, he was awarded the Brendan Walsh prize for the best paper published in Economic and Social Review. Previously, he was scientific officer at the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. He studied at the University of Florence, where he majored in actuarial and statistical sciences and attained a PhD in Applied Statistics. He has been visiting fellow at the University of Sydney and at Aalborg University and visiting professor at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

Related content

27 September 2020

This report presents the findings of the Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey, carried out by Eurofound to capture the far-reaching implications of the pandemic for the way people live and work across Europe. The survey was fielded online, among respondents who were reached via Eurofound’s stakeholders and social media advertising. Two rounds of the e-survey have been carried out to date: one in April, when most Member States were in lockdown, and one in July, when society and economies were slowly re-opening.

The findings of the e-survey from the first round reflected widespread emotional distress, financial concern and low levels of trust in institutions. Levels of concern abated somewhat in the second round, particularly among groups of respondents who were benefiting from support measures implemented during the pandemic. At the same time, the results underline stark differences between countries and between socioeconomic groups that point to growing inequalities.

The results confirm the upsurge in teleworking across all countries during the COVID-19 pandemic that has been documented elsewhere, and the report explores what this means for work–life balance and elements of job quality.